Reference Shot Practice

Now that you’ve made sure your alignment and cueing action are straight, you can take that powerful combination to the angled shots. However, never stop practicing the MOFUDAT drill and long straights. They are important routines that help keep technique in check. They are also great warm-ups before playing.

References in Stages

I think it’s best to practice the Angle Detective reference shots in stages. Beginning with all of the references, including the in-between references, may not be as effective as learning the main ones. There is even some logic to always keeping the number of references at just a few, allowing for the development of feel as the filler of the spaces between. Either way, start with the main references. Once you’ve mastered them, you can move on to the rest if you’d like.

Here are the stages I recommend.

Stage 1: Narrow your focus in the beginning to only the reference shots and aims of ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’, ‘D’, ‘E’, ‘F’, ‘Q’, ‘RS’, and ‘ST’. These are the 8 eighth-ball fractions plus ‘ST’ which is an additional 1/16-ball thin cut fraction.

Stage 2: add AB, BC, CD, DE, EF, and FQ.

Stage 3: add QR, R, S, T, and TU.

Stage 4: add the plusses and minuses.

Seeing for Yourself

It is important to repeatedly practice the reference shots under precisely controlled conditions. You want to become intimately familiar with the aim and exact angle of each reference shot, and the only way to do this is with precise ball placement when setting up your practice shots.

The angles of our reference rectangles are fixed. ‘A’ will always be 0°. ‘B’ will always be 7°. ‘C’ will always be 14°. ‘D’ will always be 21°. ‘E’ will always be 27°. ‘F’ will always be 37°. ‘Q’ will always be 45°. And so on.

Although the reference angles are fixed, the reference aims for those angles are adjustable. We find the appropriate adjustments to the reference aims as we repeatedly practice pocketing each reference shot. Is the aim for ‘C’ truly midway between the object ball’s center and its edge? Is the aim for ‘E’ truly directly at the object ball’s edge? It is important for you to answer these questions for yourself. It is also important for you to discover for yourself whether the aims for each label change with changes in spin, speed and playing conditions.

We want the object ball to be a distance from a pocket when setting up our practice shots. When the object ball is far from a pocket, any errors that we make during our practice will be magnified. This will force us to hone our technique and sharpen our aiming.

These long practice shots will be more difficult than most shots we encounter during actual play, so if we can pot them repeatedly we know that we are truly performing with precision. We need to be challenged during practice. We want to groove the reference shots into our routines and memories so that they become second nature.

When first practicing you may be surprised by how many shots you miss. Precisely setting up a 27° ‘E’ shot and knowing to simply aim at the edge of the object ball should be good enough, right? Well, when the object ball is 5 or more feet away from the pocket, you’ll find that there’s no room for sloppiness. If stroke, aim or alignment is just a bit off, misses come easily.

I suggest striking the cue ball with a medium to medium-soft stroke when first learning these shots. The object ball should not slam hard into the back of the pocket nor should it barely reach the pocket and drop straight downwards. Find a repeatable stroke speed that allows most shots to enter the pocket at a falling angle.

But when you practice the thin cuts on the far side of the Master Square, it will be necessary to increase your stroke speed in order to transfer enough energy to the object ball to get it all the way to the pocket.

I also suggest that the tip of your cue strike about a centimeter above the center of the cue ball and without side spin. This will get the cue ball quickly rolling naturally on its way to the object ball.

Standing behind the shot and before bending over to play it, quietly or mentally “speak” the letter label of the shot. This should help to ingrain the shot’s label and aim into your routine and memory.

Once you’ve found the proper aims using a medium to medium-soft speed and can comfortably and repeatedly pot the reference shots, you can move on to other speeds as well as various amounts of stun, draw and follow spins.

You may find yourself surprised (as I was) by how cue ball speed variations as well as draw and follow spins effect where you must aim to pot the very same reference shot.

Of course practicing side spins would be next, but I encourage you to master the aims for all shots along the cue ball’s vertical center axis before practicing side spins. Side spins can alter release angles drastically as well as introduce cue shaft deflection (squirt) variables, so be patient and don’t jump in too quickly.

Accurate Ball Placement

There are several ways to accurately place balls for repeated Angle Detective reference shot practice.

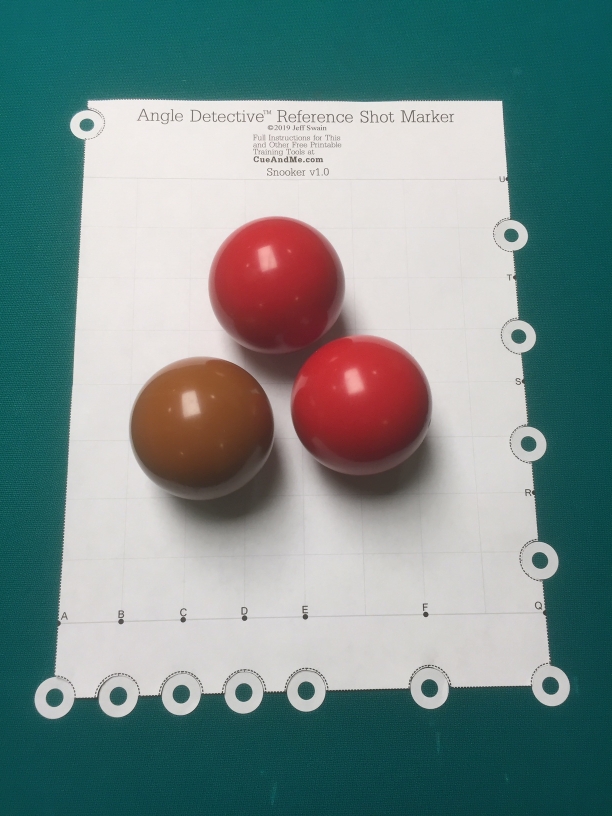

The Reference Shot Marker Tool

This is a newly designed printable tool that allows you to mark and place the object ball and cue ball for all of the main references. You will find it in the Angle Detective download folder.

The next page goes over how to prepare and use the Shot Marker tool.

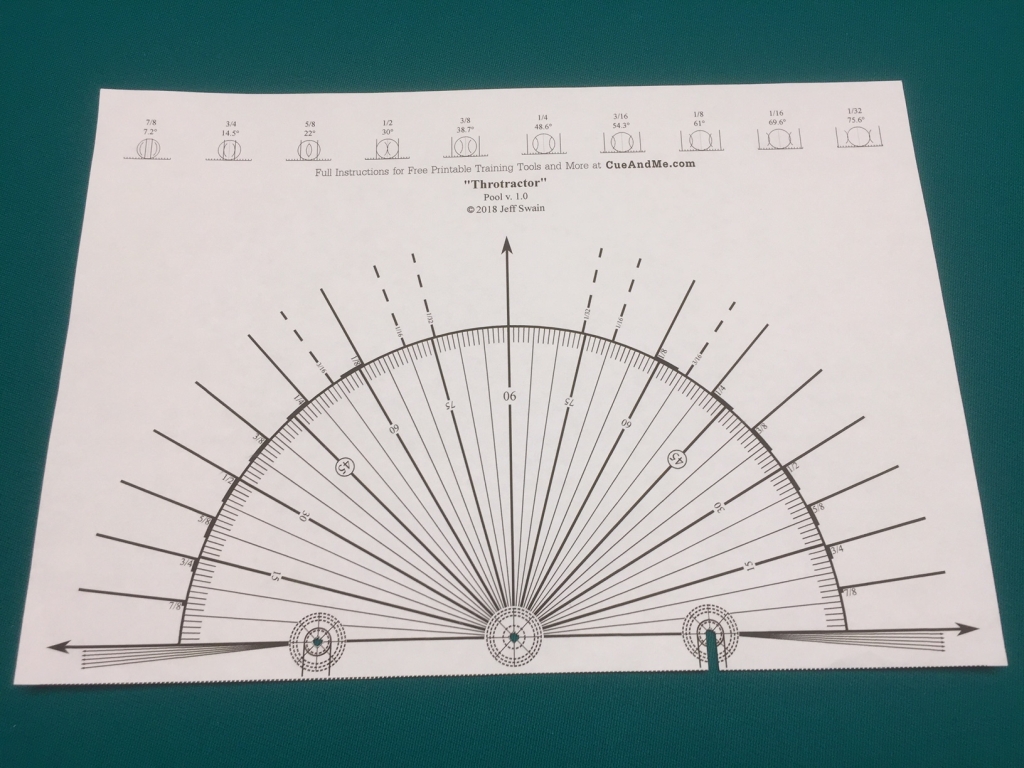

Throtractor

I designed Throtractor specifically for accurately marking the cloth for practice setups of any angle from 0° to 90° with an allowance for up to 5° of throw.

Follow the link below for instructions for preparation and use.

https://cueandme.com/billiard-training-tools/

Here again are the Angle Detective reference shot angles and aims. Simply choose a reference angle, and mark the object ball and cue ball positions using Throtractor. Throtractor allows for the use of one object ball position for several cue ball positions.

Label

A

AB

B

BC

C

CD

D

DE

E

EF

F

FQ

Q

QR

R

RS

S

ST

T

TU

U

Angle

0°

3.6°

7°

10°

14°

17°

21°

24°

27°

32°

37°

41°

45°

49°

53°

58°

63°

69°

76°

83°

90°

Aim

8/8 or Full Ball

(15/16)

7/8

(13/16)

6/8 or 3/4

(11/16)

5/8

(9/16)

4/8 or 1/2 (‘E’ for “Edge”)

(7/16)

3/8

(5/16)

2/8 or 1/4 (‘Q’ for “Quarter”)

(7/32 or Theoretical 1/4)

(3/16)

1/8

(3/32)

(1/16)

(1/32)

(1/128)

1/∞ (‘U’ for “Unmakeable”)

Label

A

AB

B

BC

C

CD

D

DE

E

EF

F

FQ

Q

QR

R

RS

S

ST

T

TU

U

Angle

0°

3.6°

7°

10°

14°

17°

21°

24°

27°

32°

37°

41°

45°

49°

53°

58°

63°

69°

76°

83°

90°

Aim

8/8 or Full

(15/16)

7/8

(13/16)

6/8 or 3/4

(11/16)

5/8

(9/16)

4/8 or 1/2

(7/16)

3/8

(5/16)

2/8 or 1/4

(7/32)

(3/16)

1/8

(3/32)

(1/16)

(1/32)

(1/128)

1/∞

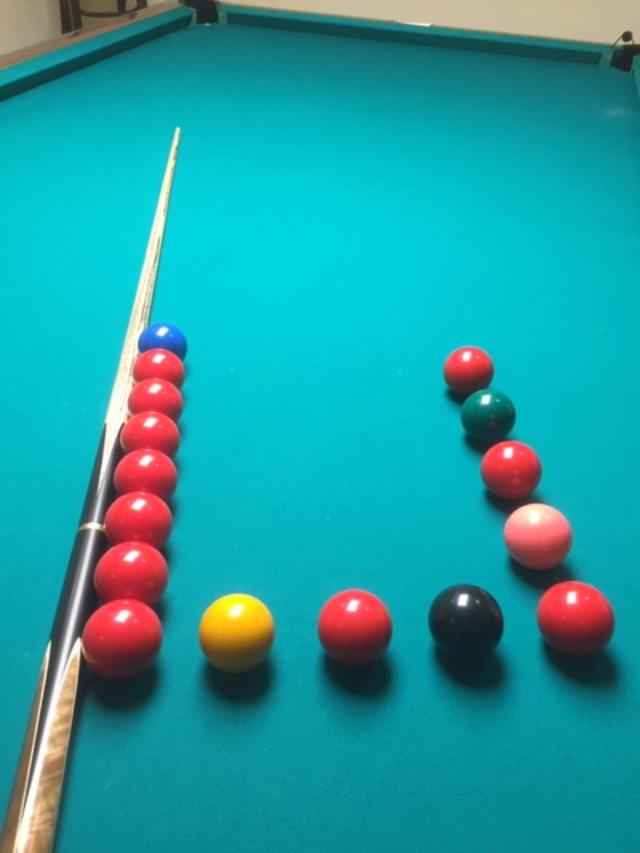

Lines of Balls

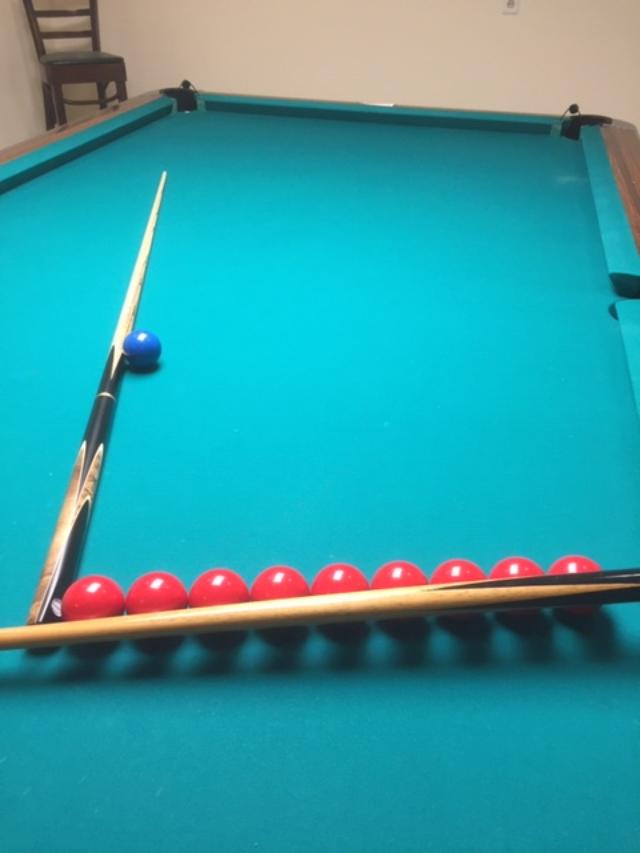

Another way is to align and rotate columns of balls. With a reinforcement label or dot of chalk, powder or removable marking pencil, mark where you’d like the object ball to rest for repeated practice. Use your stick to align an even number of touching balls so that they are all pointing directly at the pocket center with the forward-most ball resting exactly on the mark.

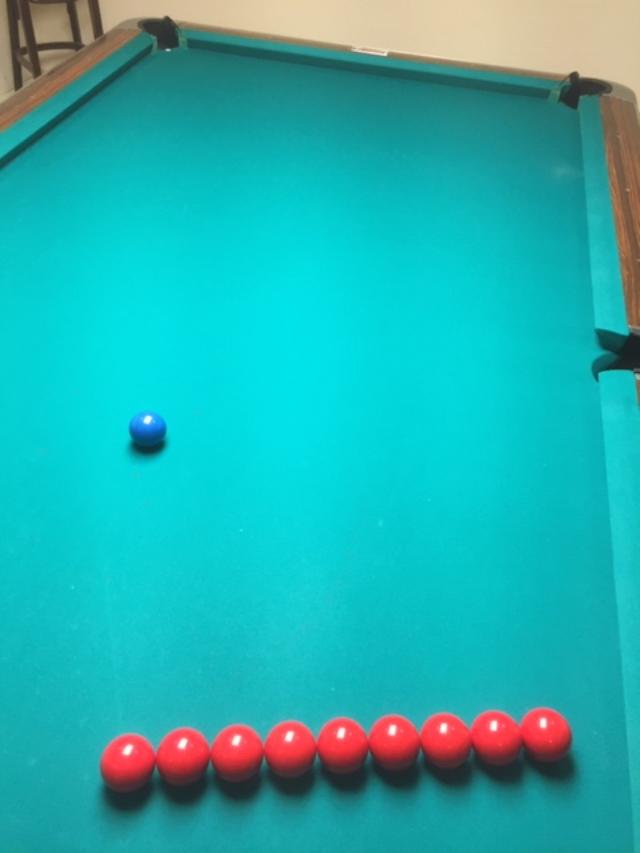

The more balls you use, the larger will be the Master Square as well as the distance from object ball to cue balls. We will look at how to do this with a line of 10 balls.

Once the line of 10 balls is pointing at the pocket, carefully remove the inner 8 balls and leave the two end balls in place. The ball nearest the pocket will be the location for the object ball. The other ball will be the location for the ‘A’ cue ball.

Careful not to move the ‘A’ ball, line up the other 8 balls next to the ‘A’ ball but at a right angle to the first line.

This creates the bottom side of the Master Square with 9 balls in the cue ball positions of ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’, ‘D’, ‘E’, ‘EF’, ‘F’, ‘FQ’ and ‘Q’.

Mark the resting positions of each “cue ball” with a dot of chalk or powder or reinforcement labels, etc.

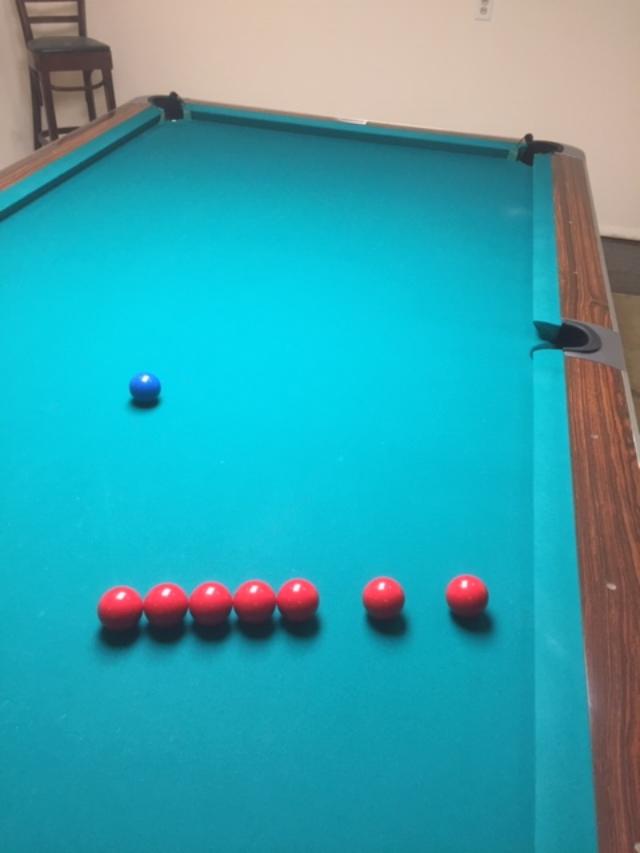

For the far side references of ‘Q’ through ‘U’, simply create another line above ‘Q’ of 8 more balls (8 balls plus the ‘Q’ ball) upward at a right angle to the bottom side. Again mark the resting positions.

Once all of the cue ball positions have been marked, you can remove all balls and begin practicing any of the reference shots or any shots that lie between the marked references.

10 balls work nicely, because each of the 9 balls along the bottom and far sides rests at a single letter or double letter reference. It also leaves a comfortable distance from object ball to cue balls. For pool balls this is about 18 to 25 inches (46 to 64cm) and for snooker balls about 17 to 24 inches (42 to 610cm).

You can also start with lines of 4, 6, 8, 12, 14, or even 16 balls. If you want to set up for practicing situations where balls are very close to one another, you would choose 4 or 6 balls.

If you want to practice shooting from a distance, you could choose 14 or 16 balls. No matter how many balls you choose the angles remain the same; only the distances between object ball and cue balls change.

The reason we use an even number of balls is that once we remove the object ball, the lines become an odd number, and only a line with an odd numbers of balls offers a middle ball (‘E’ or ‘S’) perfectly centered between the end balls. Once you have the end balls and the middle balls marked, you can locate the positions for the rest of the references by marking midway between them and subsequent marks.

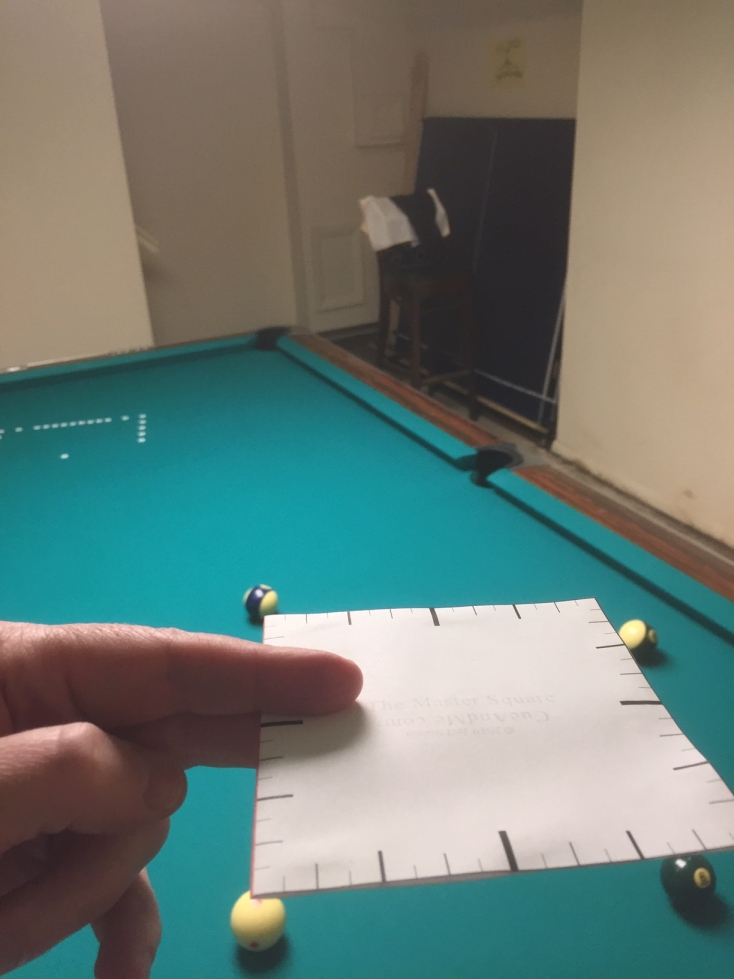

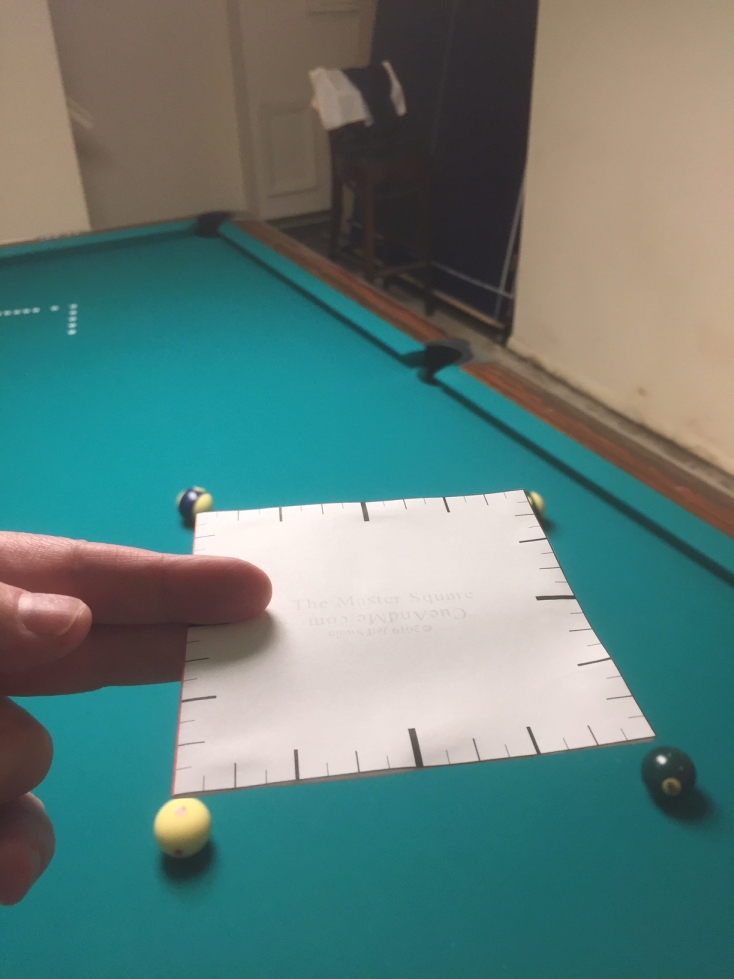

Chalk Cube Bottom or Master Square

You can also use the printable Master Square or bottom square of a cube of chalk using the hovering technique explained in the Application section. First place a mark on the table for the object ball and place a ball on the mark. Then place the ‘A’ ball in line with the object ball and pocket at whatever distance from the object ball you’d like to practice.

Next, eyeball the locations of the ‘Q’ and ‘U’ balls and place them to temporarily complete the square.

Carefully hover the Master Square or chalk bottom square until its near side matches the object ball and ‘A’ cue ball. Move the ‘Q’ and ‘U’ balls until they match the Master Square or chalk square.

Once you have the corners perfectly placed, you don’t need the Master Square or chalk anymore. You can find and place ‘E’ midway between ‘A’ and ‘Q’ and place ‘S’ midway between ‘Q’ and ‘U’. Continue marking midway at ‘C’ and ‘F’, ‘R’ and ‘T’, then ‘B’ and ‘D’.

Dual Personalities: Shot Analyst and Shot Maker

With precision practice we develop a feel for each reference shot, and the aims start to infiltrate our pre-shot routines. Proper aiming begins from the full upright standing position.

While standing or walking upright, our role is that of “shot analyst.” Once we have begun to step and bend into the shot, we should have completely shed our role as shot analyst and assumed the role of “shot maker.” The shot maker relinquishes all analyst duties and commits to the prior decisions of the shot analyst. It makes sense for the shot maker to trust the shot analyst, because the shot analyst had the opportunity to view the shot from all angles and heights. Once we are down in the shot maker position, these perspectives have been lost.

When we practice something new, it isn’t easy for the shot maker in us to commit to the decisions of the shot analyst. We should commit anyway. The shot maker must be willing to allow misses to happen so that our shot analyst can learn from his or her mistakes. As shot maker, we should train ourselves to live or die by the decisions of the shot analyst.

Conversely, while standing in the role of shot analyst, we must be sure to complete our duties before handing the shot over to the shot maker so that the shot maker can be fully convinced to trust our analysis. Finding a standing aiming position that is reasonably close to correct and then assuming that the shot maker will maneuver to adjust to the final aim does not allow our inner shot maker to fully commit. As shot analyst, we should hand the shot over to the shot maker only after we have precisely positioned ourselves so that our eyes, head and body are locked onto the final aim for the shot.

As we step and bend into the shot, we should take care to maintain our standing alignment. Smooth, precision stepping and precision bending into the shooting position should be part of our practice. If at any point our head drifts to either side, we should stand up and start again. When we practice, no aiming or head adjustments should be allowed after locking onto the aim from the standing position. It is important to be willing to stand up and start over so that the roles of shot analyst and shot maker can develop independence and integrity as well as trust in one another.

Holistic Precision

When we practice and play, although it is important to be as precise as possible, it is also important to remain relaxed and fluid.

When learning something new, we can lose fluidity if focus becomes too intense. I encourage you to allow your body to stay loose and active when practicing the Angle Detective reference shots. Don’t assume that accurate aiming and alignment requires laser focus. It requires attention, but attention from the entire body, not just the eyes.

Feel the aim with the entire body when moving into and standing in position behind the shot. Precise aiming and alignment can be achieved through a soft rather than an intense focus of the eyes. With soft focus, we have a better chance of seeing and feeling the entire shot and table rather than just a singular aiming point.

If reference shot practice engages the active and fluid body, our aiming becomes holistic rather than robotic. This allows for feel to develop.

I believe this approach is especially helpful for those of us with imperfect vision. A soft focus and a relaxed yet attentive body is enough to allow us to stand, aim and align properly.

I think of snooker’s Ronnie O’Sullivan as the epitome of holistic precision. His routine is athletic. Although he positions his body precisely, it is never frozen but always active in micro-motion, and he seems to have an awareness of the shot and table with his entire being. His eyes may even flit away from the shot line, but his body remains engaged, rhythmic and fluid.